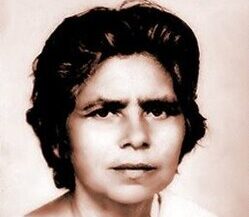

In the rolling green highlands and sun-baked plains of Western Odisha, where the Mahua trees whisper secrets of the past, the name Parbati Giri is spoken with a reverence usually reserved for the forest deities. She was not born into wealth or high status; she was a daughter of the red soil, born in 1926 in the humble village of Samlaipadar.

From the very beginning, the rhythm of her life was dictated not by the domestic hearth, but by the thrum of the spinning wheel and the distant roar of a nation awakening. While other girls her age were tethered to the traditional roles of the village, Parbati was a spirit of the wild winds, leaving her home at the tender age of eleven to join the Bari Ashram. It was there, under the maternal gaze of Rama Devi, that the young tribal soul was tempered into a weapon of non-violent resistance, earning her the enduring title of Banhikanya—the Daughter of Fire.

This fire did not burn with hatred, but with a fierce, unyielding love for her people and her land. During the height of the Quit India Movement in 1942, the fire reached its peak. At only sixteen years old, Parbati Giri did the unthinkable: she marched into the British stronghold of the Bargarh SDO office, not as a prisoner, but as a self-appointed judge.

In a scene that has become a legend in Odia folklore, she occupied the magistrate’s chair and demanded that the colonial officials vacate their posts and join the people’s struggle. Her defiance was so raw and her spirit so untamed that it rattled the very foundations of British authority in the region. She faced the darkness of the prison cell with the same stoicism with which she faced the forest summers, never once wavering in her commitment to the Gandhian ideals of Khadi and Swaraj.

Yet, when the dawn of independence finally broke over India in 1947, Banhikanya did not seek the spotlight of the new government or the comfort of a political throne. Instead, she returned to the dust and the trees, understanding that true freedom meant nothing if the stomach was empty and the soul was neglected. She became the “Mother Teresa of Western Odisha,” a healing hand for the orphans, the leprosy patients, and the forgotten tribes of the hills.

She founded ashrams that became sanctuaries for the destitute, walking miles through rugged terrain to serve the “Antyodaya”—the last person in the line. Even today, though she has returned to the earth, her legacy remains etched in the Gandhamardan hills, a reminder of a girl who was born in the shadows of the forest but lived her life as a brilliant, scorching flame of justice.