At dawn, when mist still clings to the sal and mahua trees of northern Odisha, the forests of Mayurbhanj and Keonjhar echo with a quiet rhythm of life that has flowed uninterrupted for centuries. Here live the Ho people, one of Odisha’s oldest and most resilient tribal communities, whose culture is deeply rooted in the soil, the seasons, and the spirit of the forest. To understand the Ho tribe is to understand a way of life where nature is not merely a resource, but a living companion.

The word “Ho” itself means “human being,” a simple yet profound expression of identity. It reflects a worldview that places humans as part of a larger natural order rather than above it. Traditionally inhabiting the forested belts along the Odisha–Jharkhand border, the Ho people have sustained themselves through agriculture, forest produce, and collective living, preserving a balance between survival and sustainability long before these ideas became modern concerns.

The Ho language, Ho or Warang Chiti–influenced dialects of the Munda family, is more than a means of communication; it is a vessel of memory. Folktales, songs, and oral histories passed from elders to children carry stories of origin, bravery, and coexistence with nature. Even today, under the shade of village trees or during festivals, these stories come alive, ensuring that the wisdom of ancestors continues to guide the present.

Agriculture lies at the heart of Ho life. Fields of paddy stretch alongside forest edges, cultivated with traditional knowledge that respects the land’s limits. Men and women work together, reflecting a strong sense of community and shared responsibility. Forests provide more than food, they offer medicinal herbs, fuel, and spiritual meaning. Sacred groves are protected with deep reverence, believed to be the dwelling places of ancestral spirits, and no tree is cut there without ritual consent.

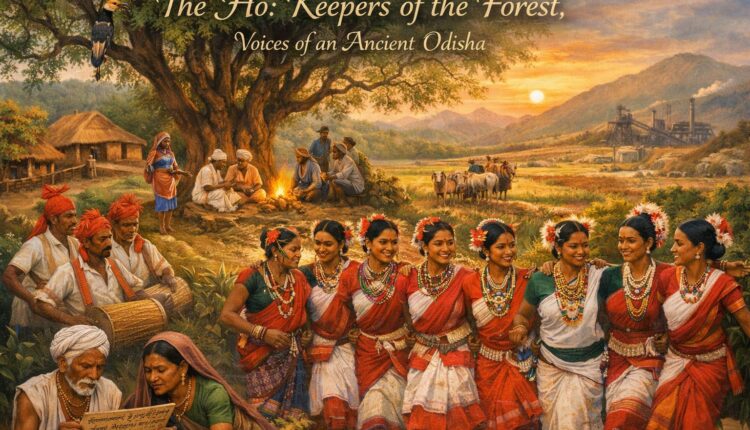

Festivals among the Ho are vibrant expressions of gratitude and joy. Mage Porob, their most important festival, marks the harvest season and brings villages together in celebration. The beat of drums, the swirl of traditional attire, and the unity of group dances transform open grounds into living canvases of culture. These dances are not performances for an audience but collective prayers, celebrations of life, land, and togetherness.

The Ho society is rich with indigenous governance systems that emphasize consensus and respect for elders. Village heads and councils play crucial roles in resolving disputes and maintaining harmony, reflecting democratic values rooted in tradition. Women, too, hold significant roles in social and economic life, contributing to decision-making and cultural continuity.

Yet, like many indigenous communities, the Ho people stand at a crossroads. Rapid industrialisation, mining activities, deforestation, and migration have begun to alter their traditional landscapes. Younger generations are increasingly exposed to modern education and urban aspirations, creating a delicate tension between progress and preservation. While education has opened new opportunities, it also risks distancing youth from their language and cultural practices.

Despite these challenges, the Ho community continues to assert its identity with quiet strength. Efforts to document their language, promote tribal art, and protect forest rights are gaining momentum. Cultural pride remains deeply embedded, visible in everyday rituals, songs sung during work, and the unwavering bond with their ancestral land.

The story of the Ho tribe is not just a tribal narrative, it is a reminder of Odisha’s deep civilisational roots and its enduring relationship with nature. In their simplicity lies profound wisdom; in their traditions, a roadmap for sustainable living. As the modern world rushes forward, the Ho people stand as gentle custodians of an ancient truth: that progress is most meaningful when it walks in harmony with the earth.

To preserve the Ho culture is to preserve a living heritage of Odisha, one that teaches us to listen to the forest, honour our roots, and remember what it truly means to be human.